Mmm, RNA

09 May 2021I like the mRNA vaccines and do not think they are risky, even though they use new vaccine technology. Here’s what I know about them.

I am not a vaccinologist or anything close, so this is just the summary of someone who reads too much Wikipedia. But hey, that’s all of us this year, so maybe it’s still useful. I welcome any corrections.

Actually my favorite source on vaccine development is not Wikipedia, but Derek Lowe’s blog. He is a scientist who has worked on drug discovery for many years. His blog is exceptionally helpful, accessible, and frank. I’ll be linking to several of his posts.

How they work

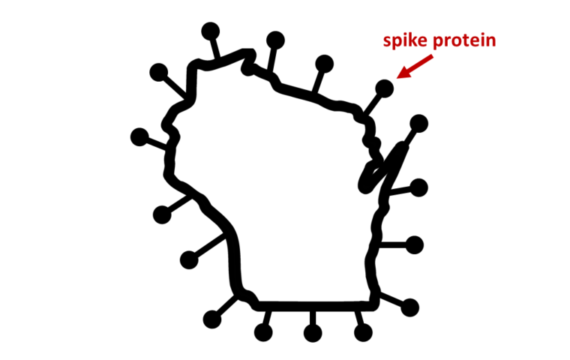

The mRNA vaccines deliver mRNA molecules, bound up with some fats, into your cells. Recalling from high school biology, mRNA is short for messenger RNA, and its normal purpose is to transfer instructions for making proteins from the permanent DNA in the nucleus to a cell’s ribosomes, where the mRNA is translated into the sequence of molecules to build a specific protein. In the vaccine’s case, the mRNA codes for the coronavirus “spike” protein, which is the spiky bit in the virus cartoons that you see, and helps the virus enter our cells.

The spike protein then finds its way from the ribosome to the cell surface, where it triggers an immune response. The reason we inject vaccines into a muscle, I recently learned, is because that keeps all this activity localized to that muscle and nearby lymph nodes. The vaccine and spike protein don’t go circulating through the whole body.

HmmRNA?

Now playing around with genetic material may sound a little dicey. There’s even a claim that these are not proper “vaccines” at all, but more like gene therapies. But I do not think this is accurate. First, the mRNA in these vaccines is not DNA, does not enter the nucleus, and therefore cannot get incorporated into a cell’s genome. It enters the cell, floats around until it gets taken up by a ribosome, and then gets translated into spike protein.

In fact, inserting RNA into our cells is also exactly what the coronavirus does. That’s how viruses replicate - they insert their genetic material into our cells, where it gets translated into viral proteins. Unlike the vaccine, however, the virus itself codes for many different proteins, so that the cell will build new whole viruses. These accumulate until the cell bursts and releases them to infect other cells.

So sure, all things equal, I would rather not have foreign RNA inserted into my cells. But I would rather have it be the RNA for exactly one protein, precisely selected to prime my immune system to avoid a disease, rather than the entire genome of a hostile infectious cell-killing uncontrollably replicating invader.

Inserting RNA or DNA into our cells is also exactly what many standard vaccines do. Many common vaccines, such as measles, rubella, one type of polio, and smallpox back in the day, are “attenuated virus” vaccines. This means they contain active virus that has been weakened or altered - bred in a certain sense, by letting it evolve in human cell lines in a lab - to not cause disease. It does still infect you, though, by inserting its genetic material into your cells and replicating.

So while our attenuated-virus vaccines have shown to be very safe, they are still active viruses, and they can have a remote risk of regaining virulence and causing disease after all. That can’t happen with the mRNA technology, which gives it an intrinsic safety advantage.

VroomRNA

The contrast between these types of vaccine also helps explain why development was so quick for the Covid vaccine. Part of the reason that vaccines usually take so long to develop is that the “breeding” of these attenuated viruses can take a long time, and is difficult to steer in the desired direction.

For the mRNA vaccine, in contrast, the difficult part was knowing which protein to target. But we knew to target the spike from previous work on the original SARS. After that, it was only a matter of sequencing the virus gene for the spike, manufacturing the mRNA, and doing the testing in clinical trials.

The testing was actually the longest part of the process. It was sped up with lots of money, lots of volunteers, and lots of coronavirus circulating - not, as far as I know, by any reduction in rigor.

HarmRNA?

These clinical trials, as well as ongoing monitoring as the vaccines roll out, has satisfied me so far that these vaccines are indeed safe. To begin with, the trials enrolled tens of thousands of people and found no safety issues (and also phenomenal 95% efficacy at preventing Covid).

Now, these trials cannot rule out very rare, one-in-a-million side effects, for the good reason that tens of thousands is less than a million. But by now the vaccines have been given to hundreds of millions of people, so we should start to see any rarer effects if they exist.

The most serious side effect discovered so far is a risk of blood clots connected to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, which does not even use the mRNA technology. For this side effect, the worst prevalence by age and sex is 11.8 cases per million shots in women 30-39.

So let’s compare that to the risk of Covid. For the age group 30-39 in Wisconsin, so far there have been 47 deaths and 94000 cases recorded. We know the cases are an undercount of infections, so multiply by, say, 4. That comes to 125 deaths per million Covid infections.

There’s uncertainty here, particularly in how many more clotting cases may be unreported. But I am comparing all the clotting cases (not just deaths), for the worst-hit age group, which is a relatively low-risk age group for Covid…and Covid is still 10x worse. And this wasn’t even an mRNA vaccine! It seems to me they are looking pretty good.

- FDA authorization memorandum for Moderna, containing the clinical trial analysis.

-

Derek Lowe’s post on getting vaccinated. Key passage:

For people who are honestly wondering about real immunological issues, though, I wanted to say that as someone who’s been doing drug discovery work for over 30 years now, and who has been covering the vaccine developments in detail with great interest during the entire pandemic, that I had no hesitation about rolling up my sleeve.

The long and short of it

The one area of risk where we do not have data is for very long-term side effects, for the good reason that there hasn’t been a long term yet. It’s possible that after some months or years some ill effect of the vaccines will show up.

But doesn’t that have to be even more true of Covid?

Which is more likely to have unknown long term effects? A dose of mRNA that makes your body produce some spike protein one day in your shoulder muscle? Or a virus that delivers the same mRNA and more besides, wildly replicates throughout your respiratory tract over the course of at least a week, and even kills a percentage of its hosts?

From what I have learned about how they work, I see no reason that the mRNA vaccines would be any less safe than other vaccines. The data we have supports their safety and efficacy. And to the extent that they may have unknown risks, simply from being new, I think the new coronavirus is clearly much riskier.